Pacing in D&D is a broad topic that can be put into three subsections.

Combat pacing.

Session pacing.

Campaign/plot pacing.

Story and session pacing is a little bit similar, but there are some important differences.

When handling pacing in D&D look at your players. If they are not engaged there is a problem. If there is no problem the pacing is great!

How do you learn to read your players?

Play by feel

Some people tell others to ‘play by feel.’ Does the table or pacing feel wrong? If so find a way to fix it!

This is extremely unhelpful for new dungeon masters or new people in a new group since you can’t accurately feel the room without any training.

This is why I have a few tips on how to feel what your group, table, and players want.

Players set the pace

Many dungeon master’s try to set the pace in their world by having the players to go along a straight and narrow path. There is nothing wrong with a linear style of play, but sometimes our plans are thrown out the window when players decide to either:

- Take forever in order to accomplish their goals.

- Do something insane that solves or tosses out the current plot.

In the first instance, players take way too long to accomplish something. For those experienced dungeon masters, how many times have you planned out a session only for your group to get halfway through what you had planned?

This is a common occurrence and can frustrate many dungeon masters since they believe that the encounters were not done right or they could have made it easier for the players.

The truth of the matter is that your players will take their sweet time to get through anything and that is okay. No everyone can move at lightning speed or see the game in black and white mechanics. These players are people too with their own ideas. These ideas may lead to inefficiency, but that is okay.

In the second instance, players are creative and just solve a problem.

Perhaps the big bad guy just steps out to taunt the players and the players collapse the big bad guy’s escape route. The big bad guy now has to face the players and the players somehow win. That plot thread is now gone, and this happens all the time.

If your players show initiative and creativity reward them for it. Do not punish the players or make a big bad guy just teleport out of there if that big bad didn’t already have a backup.

Either way, you will find out very quickly what type of group you have. Most people have the first type of group and might need to speed up the game. If not, the game will not end in a decent spot and everyone will start to get bored if nothing happens for too long.

Focus on the players

Players generally get bored when they do not have the dungeon master’s attention. How many times have players pulled out their phones or something else because they were bored?

This is because the pacing in D&D failed them.

Generally, dungeon masters fail their players by becoming too focused on the world and not the players.

Dungeon master’s try to force their hard work onto the players by dumping lore, exposition, and other boring things onto the player’s heads. Players don’t care about these things unless they are slowly revealed and personal.

Why would player care that Mcdufferson is the mayor of Shantytown? The answer is that the player would not. If the players start to adventure in Shantytown and see that the town is a terrible place to live they might get curious.

The players will then start to learn about the situation of the town and be asked to pay exorbitant taxes by MCdufferson. Now the players have a personal interest in the lore and want to interact with the world around them.

Always have the game focus on the players. When I run my game the world can move without the players. Players can influence the world, but the world does not revolve around them. My table, on the other hand, revolves around my players.

If you run an uncaring world like I generally do make sure that your players are the center of their world. Do not make them feel small and instead focus on them.

Once you do so the pacing of your game will become more natural since it is focused on them, your players. Once the players are the focus pacing will become more natural.

But how do you have decent pacing in combat when the players are already the focus?

Combat pacing

Pacing in D&D combat is fairly simple and follows a few basic rules.

More monsters = more turns = more time.

Less players= less turns = less time

More engagement = less wasted time

Extra rules and tools are only used to engage people. When we implement rules like “you need to know what to do on your turn or if you can’t answer in 10 seconds you are skipped!” Or having an initiative board to show people who are up next are only used to engage people more.

If your combat has interesting mechanics and keeps your players engaged you will not need any of these things. If you want to figure out how to make combat more interesting and retain player engagement read this combat article.

Once your players are engaged you can lose their interest if there are too many players or too many enemies. There is a reason why most games do not have large groups of people.

If there are 8 people in your group, you need to wait for 7 other people to do their turns before you get to do something. Most people just pull out their phones when they are waiting since this will take a while.

Conversely, if you are the only person in a game and there are 10 monsters/NPCS you might take out a phone since this is going to take a while. Granted in this state those 10 monsters might affect you so you need to pay attention, but it is still boring and not very engaging.

If this is the case, how long does it take to finish an encounter?

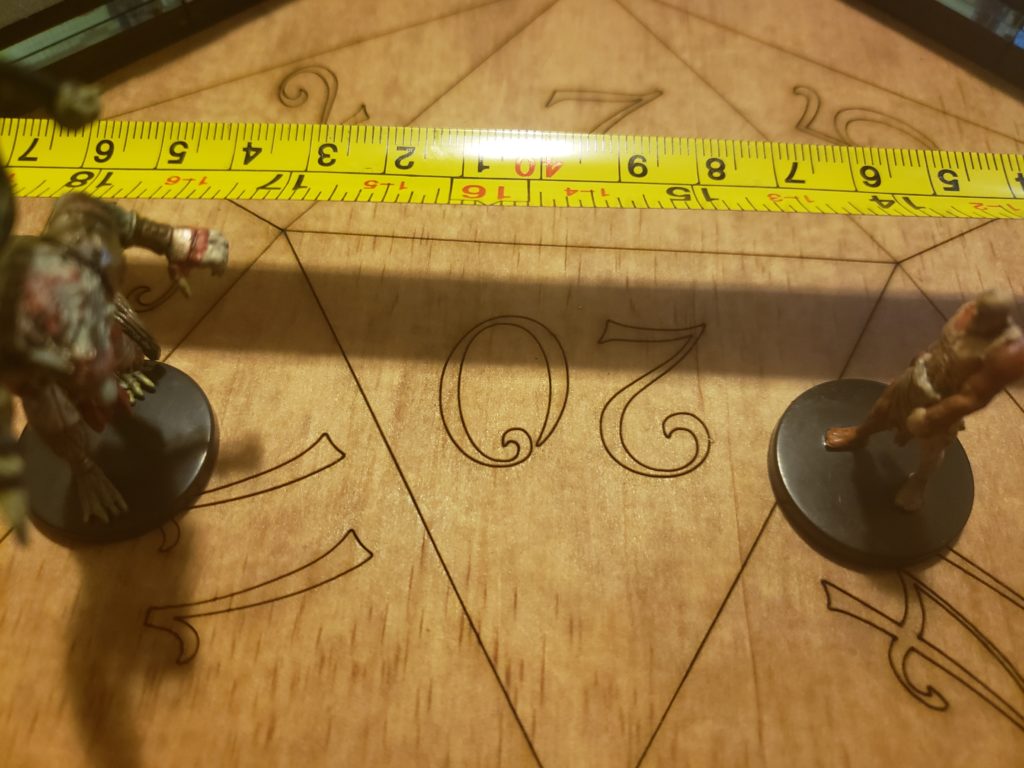

Combat length

Combat length in game is relatively short. Each round is 6 seconds in game so your group might take one minute in game to finish most combats. This is the exact opposite of what happens in real life.

When you are trying to handle pacing in D&D, combat can eat up most of your session time.

A good rule to follow is that for 4 players a medium/hard combat should take you an hour in 5th edition.

The good news is that 5th edition has the quickest combat out of the three most recent editions. Third edition is much longer. It can be 2-3x as long.

If you are concerned about combat length hampering the pacing of your game do 5th edition. Combats are easier to finish than in previous editions and make one minute in game ONLY equal 1 hour in real life.

If you need to pick up the pace or make combat more interesting read this article. As an extra tip to help speed up the game, take your monster’s turns on the player’s turns.

Roll their attacks, have their spells ready, do everything so that when the monsters turn comes you finish their turn in a flash and make the players the focal point of combat. This will spur them to move faster and be more engaged.

But what happens before combat? What about the pace of your game when players are planning and strategizing?

Session pacing

Player discussions

Players will generally want to make some sort of plan before they fly headlong into any situation. If the players have enough information they can completely destroy your pacing in D&D.

Players will agonize over what to do when they have even a tiny bit of information and some time to plan. I have seen some ridiculous planning that has taken over an hour in game, and some planning that has taken fifteen minutes.

Bottom line, players will take a while to plan anything. There are a few ways to deal with this and not have it completely destroy your pacing.

The first option is to not let them plan. This is generally okay since planning is not always possible. “An owlbear comes out and strikes at Bregor. Roll initiative!”

Now the party cannot plan and if you have taken some advice from the combat article your players shouldn’t really plan too much in combat.

The first option is not always ideal, and your players will want to plan eventually. That is where the second option comes in. Not enough information.

Your players cannot plan if they do not know enough and will either back off or charge headlong into chaos. This depends on the group, but most groups charge into chaos since, well, they are players.

A third option is that you end the session in a manner so that your players can plan big decisions at a break (if you have one) or in between sessions. Leave them with a cliffhanger or something to ponder.

Many players talk outside of session and have a week or more to figure out what to do next. This is a great solution that lets you keep control of the pace since you know when they will be able to plan and end your session on time.

Sometimes the room becomes quiet when players are at an impasse or just done strategizing. If you do not pick up on this they will go to their phones and quickly lose interest completely slowing down the game.

IF THE PLAYERS ARE QUIET, ASK WHAT THEY ARE DOING!!

When your players are quiet they are probably done talking. If you do not pick up on this the players are being told that the game is a slower paced game. If you do not want a slow paced game you have to interact with them right away. Keep them on their toes and make sure that there is no boredom.

But what do you do when they lose focus?

Keeping attention

Keeping your player’s attention is crucial to pacing. If your players are scatterbrained they will not get through anything and might make those three hours you were going to play only become two hours.

This destroys any semblance of pacing in D&D. You planned for them to go through combat and do some noncombat encounters? Well, now you might finish the game halfway through combat.

Starting a game in new combat or right after old combat is fine, but mid-combat? Everyone has forgotten what they are doing, what resources they have, who the enemy is, and it is just a mess.

This begs the question, how prepared should you be before each session?

Preparation

Generally, you should have an idea where each session will go. You can also estimate that the players will, or probably will get through a certain amount of content. Here is the hard truth:

You will always be wrong.

When you try to control pacing in D&D by anticipating your players you will always fail. Players somehow have a magical ability that tells them if you have nothing prepared, or three sessions worth of plot prepared.

If you have nothing prepared and just plan to wing it by the environment your players will move at lightning speed through everything covering 4 sessions worth of pacing and plot in one.

Conversely, if you prepare one session’s material your players will take 3 or more sessions to get through the content.

You will always be wrong, and your players will always surprise you. This is why I always say to at least have two sessions worth of material planned in order to make sure that your players don’t blaze through everything and get bored.

Having a plan will also help you cut off the session and end it when need be.

Description

We all love describing things as dungeon masters to our players and that description is crucial. If you only relay that the players enter a square room, there are going to be a lot of questions.

If instead, you tell your players that they have entered a plain room with a bed in a corner, chamber pot, and a coat rack that holds a few articles of clothing the room now paints a picture.

Descriptions certainly deserve an article of their own, they can also detract from the pacing of your game.

If you describe too much, the game can fall flat. Pacing in D&D needs to be kept fluid. If the players start to get bored because there are too many details they will just do something easy like look at their phones. If the descriptions are too much, it can also confuse your players.

Do not go too far into descriptions. If you are able to tantalize players that is better than losing them. Players only need an understanding of what the situation is in order to make decisions.

If you, on the other hand, do not give enough description players will start to pull out their phones and not pay attention.

You need to hit that Goldilocks zone. Make sure your players are paying attention and force them to make decisions with your descriptions.

Your descriptions are meant to give enough information on the scene so that your players act. The clearer your description is, the easier it is for the players to act and not interrupt the pace of your game.

If you do not give enough, or too much description you might endure the 10000 checks problem.

10000 checks

If players are curious about a room because it is too bare or has too many interesting objects you will encounter the 10000 checks problem.

Many sessions’ pacing is disrupted when one player fails a check, then another player decides to roll for a skill, and then if they fail this may continue forever.

This does not generally destroy the game’s pacing but instead causes minor roadblocks. The problem is that if the players encounter enough interesting items 5 minutes multiplied by 4 can equal 20 minutes of session time being eaten up for something that is not necessary.

It is good for your players to be curious about things in their world but the pacing in D&D might have a strict time schedule. If you are in a time crunch or have limited play time make the players only roll once for a skill check (possibly with help if stated beforehand) or make some time pressing event happen.

If you are not in a rush, players checking everything can be okay. just do not give them too many objects to work with.

Now to end the session.

Ending a session

Always end a session in suspense or ponderance.

Give your players something to talk about so that your pacing in D&D is not affected in-game. Players will need a breather to think and digest some heavy material.

Players also need a breather after heavy combat. Give that to them at the end of the session. As mentioned earlier players will possibly talk about the game outside of game time. If your players are pumped up to discuss the game after it is done like people do with a good film or game, you are doing a great job.

Always end the session early.

If you plan to end the session a little bit early, you will almost never go over time. If you plan to end the session at the proper time you will most likely fail. By planning an early end you will stop that rush at the end of the night and make the ending feel more organic rather than panicked.

If you had to choose between dragging out a session or ending it early with some sense of suspense or closure which would you choose? Most would choose the later.

When considering your pacing in D&D make sure that you end on a brief high note instead of a long drawn out thud.

Campaign pacing

I know that I have only talked about session pacing in D&D and not campaign or plot pacing. Some aspects are interchangeable, but most of the previous advice was focused on session based pacing tips. Now we get into pacing your campaign.

Let me just put this out there right away, Your campaign is as slow or fast you think it is.

If you think that your campaign is going too slow, you are most likely correct. If your campaign is going by way to fast since your players don’t know what is even going on, you are most likely correct. Lastly, If you do not think your campaign is too fast or too slow, you are most likely correct.

Take a moment and think about your campaign. Is it going too fast or too slow? Leave a comment below and say why the game is going too fast or too slow if the pacing is off.

Some people will say that campaign speed doesn’t matter and I highly disagree.

Do you think it is better to have a fast or slow campaign?

Fast or slow?

Many people when pacing in D&D don’t even think about how important campaign speed is. If you make your campaign take absolutely forever it will never finish. People will leave satisfied since nothing ever came of it. If you finish too fast people will wonder what is the point of that campaign. So which should you choose? Fast or slow?

Fast is much better than slow.

If you create a fast campaign you can make some mistakes, but they will be over quickly. If you make mistakes you can learn from them and improve much faster. A shorter campaign is also easier to plan for which makes it more likely to finish.

A long campaign might be epic in scope and every dungeon master wants their players to complete this grand saga but most of the time these campaigns never finish. That saga is never realized.

While some players may have fond memories you are haunted by the fact that your game could have become so much better if they just played for another 6 months!

I might be haunted by this failure, and that is why I am extra harsh on myself to only make short campaigns. I may be personally haunted, but here is what I have found out over the years. Short campaigns turn into big campaigns.

Players only see the initial benefit of what they do. It is not their fault that they do not see the grand design, and that is okay. The game’s narrative builds as one narrative block at the time. You cannot make the top of a building before you make the base. Focus on the base.

You can have an overall idea of a grand plot, but do not put too much planning into it. If you make a bunch of short and fast campaigns you add more blocks, more depth, and the players get more satisfaction.

Group capability

Some groups are more capable of getting through plots than others. This does not mean one group is better than the other, just more focused. If you have a focused group your players will get through a 10 session campaign in 5-8 sessions.

If your group is a not so focused group they can take anywhere from 13-20 sessions to finish the plot. A balanced group will finish a plot in around 10 sessions from this ratio, but it is crucial to find out what type of group you have.

If your group is on task and able to speed through encounters efficiently then your group is most likely a focused group.

If your group has some creativity but lacks execution, or attempts to execute a task while having some miscommunication and mayhem in encounters you are in a typical group.

Lastly, if your group does not care about the plot and just wants to enjoy the game, you have an unfocused group.

What group do you have? Leave a comment below.

Getting through a campaign quickly, moderately, or slowly is important since it will tell you what type of plot to run.

If your players are fast, be ready to have action-packed campaigns that can become something more than usual campaigns. In one year this group might get through 1 ½- 2 years of content which allows you to develop some ridiculous plots which normally would never happen.

Normal paced groups are normal.

Slower groups are able to get sidetracked on many side quests, missions, and possibly make a whole campaign out of misadventures. Imagine a story where the main character has a mission but ends up helping many people and does many different things before they finally focus on that mission. That is this group. Weave a story around each interaction and do not expect the plot to be the main focus.

Conclusion

Pacing in D&D can be broken down into three sub-categories:

Combat

Session

Plot

Each has its own pacing considerations. I hope that I was able to help you identify what pacing your group has and help you keep your combats, sessions, and campaigns/plots on track.

This has been Wizo and keep rolling!